Concurrency and parallelism in ROS 1 and ROS 2: Linux kernel tools

This is the second (and last) article in a series that tries to give developers the right knowledge to tackle performance (especially latency) problems with ROS. The first article covered the journey from the ROS API to Linux threads. This article will complete the quest by introducing how these threads are mapped to Linux threads.

This article is partially based on my presentation at ROSCon 2019.

The toolbox

As we've seen in the previous article, the ROS API offers CallbackQueues and

Spinners to control how specific callbacks and topics are mapped onto OS

threads. The next step is to control how these threads are mapped to CPU cores.

That's the job of the OS scheduler, which keeps a list of active threads

waiting for CPU time, and multiplexes them on invidual CPU cores.

Since resuming, swapping, or pausing a thread incurs quite a bit of latency, the choices made by the OS scheduler have a big impact on the overall performance of the system. The best option is just to avoid the problem altogether. As long the stack doesn't spawn more threads than there are CPU cores, the job of the scheduler is easy. Since one thread = one CPU core, application-level APIs (eg. spinners) are enough to give the developer full control over the CPU.

However, I've never seen a ROS stack that manages to achieve this goal. In ROS 1, even the simplest C++ node spawns at least 5 threads. Granted, most of them are IO-bound (for example waiting on network sockets), but that's still quite a lot of threads for the kernel to manage. This means that we'll need to introduce OS-level tools to control how threads are mapped onto CPU cores.

The next sections will introduce the 4 most commonly used tools to achieve this goal:

- thread priorities

- the deadline scheduler

- a kernel with real-time (

PREEMPT_RT) patches - CPU affinities and

cpusets

Thread priorities

Assigning thread priorities is the most intuitive and widely known tool to

control scheduling. Threads with higher priority tend to get more CPU time

over time (we'll see more about this later). Priorities can be set with the

nice command line tool or the setpriority(2) syscall.

While priorities are useful for workstations and servers, they're not sufficient

for robotics applications. The default scheduling algorithm in Linux

(SCHED_OTHER) is based on time-sharing, and therefore allows a low

priority thread to steal CPU time away from an higher priority one as long

as the overall allocation of CPU time is consistent with the priorities.

This is obviously undesiderable in Robotics systems, where high-priority operations are often critical for safety. Luckily, Linux offers other scheduling policies that offer more control to the developer.

The deadline scheduler

The deadline scheduler (SCHED_DEADLINE) is an alternative scheduler that

individual threads can opt in to. Deadline-scheduled threads inform the kernel

that they require n microseconds of CPU time every time period of m

milliseconds. After running a schedulability check to ensure that all

deadline-scheduled threads can co-exist on the machine, the scheduler

guarantees that each task will receive its time slice. Deadline scheduled tasks

have priority over all others in the system, and are guaranteed not to

interfere with each other (ie, they're preempted when they exceed their time

allocation).

For reference, it's actually fairly straightfoward for a task to opt in to the deadline scheduling class. Here, the task declares that it needs 10 milliseconds of CPU time every 30 milliseconds. Depending on the system configuration, these calls might need root-level permissions.

struct sched_attr attr;

attr.size = sizeof(attr);

attr.sched_flags = 0;

attr.sched_nice = 0;

attr.sched_priority = 0;

/* This creates a 10ms/30ms reservation */

attr.sched_policy = SCHED_DEADLINE;

attr.sched_runtime = 10 * 1000 * 1000;

attr.sched_period = attr.sched_deadline = 30 * 1000 * 1000;

int ret = sched_setattr(0, &attr, flags);

Real-time capable kernel

SCHED_DEADLINE is an improvement over the deadline scheduler in terms of

latency, but there's still a problem. The kernel itself is still allowed to

interrupt user tasks when it needs to run housekeeping chores and service

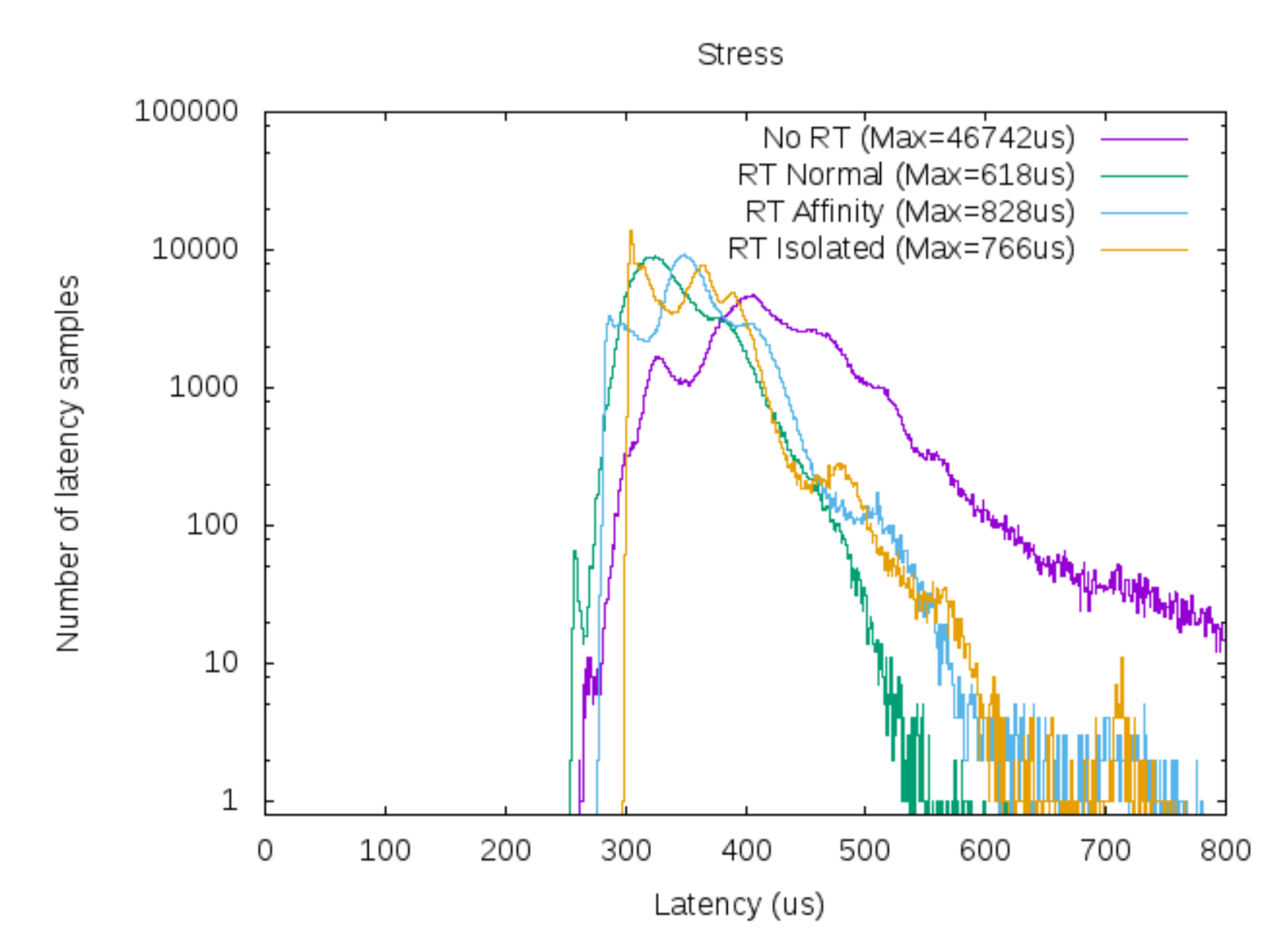

syscalls. As shown in the following figure (from 1), this means that user

tasks can suffer from unbounded latency (purple line) when the kernel suspends

them to complete long-running tasks in kernel mode.

This issue is somehow alleviated by the PREEMPT_RT set of patches to the Linux

kernel (green line in the figure). By making more kernel operations

interruptible and scheduling them alongside user tasks, these changes provide an

upper bound for latency (the tails of the latency distribution die off). A

PREEMPT_RT kernel trades these improved latency guarantees for a decrease in

throughput because of the increased synchronization overhead.

CPU core affinity and cpusets

The previous 3 sections covered tools to control how the OS scheduler decides which tasks to select for execution at any given time. On a multicore CPU (which is most of the CPUs today, even on robots), the missing piece of the puzzle is choosing which of the CPU cores should execute a certain task. This decision can have a big impact on performance because modern CPUs rely strongly on large caches for performance. Swapping a task from one core to another invalidates these caches and therefore makes code run substantially lower.

The sched_setaffinity family of syscalls and the cpuset machinery in the

kernel are the two main knobs that can be used to tweak the allocation

heuristics in the kernel. Besides an increase in throughput, this also helps

limit interference between different components of the stack.

Wrapping up

This completes the journey from the ROS interface down to execution on CPU cores. The first article covered ROS-level APIs to control how subscriptions are mapped onto Linux threads. This article took it all the way to the hardware by presenting the most important knobs in the Linux kernel.

While our coverage of these complex topics could never be extensive, hopefully these pointers will be a good starting point for Roboticists struggling with performance issues on their robots.

References

Carlos San Vicente Gutiérrez, Lander Usategui San Juan, Irati Zamalloa Ugarte, Víctor Mayoral Vilches, Real-time Linux communications: an evaluation of the Linux communication stack for real-time robotic applications